About the Project

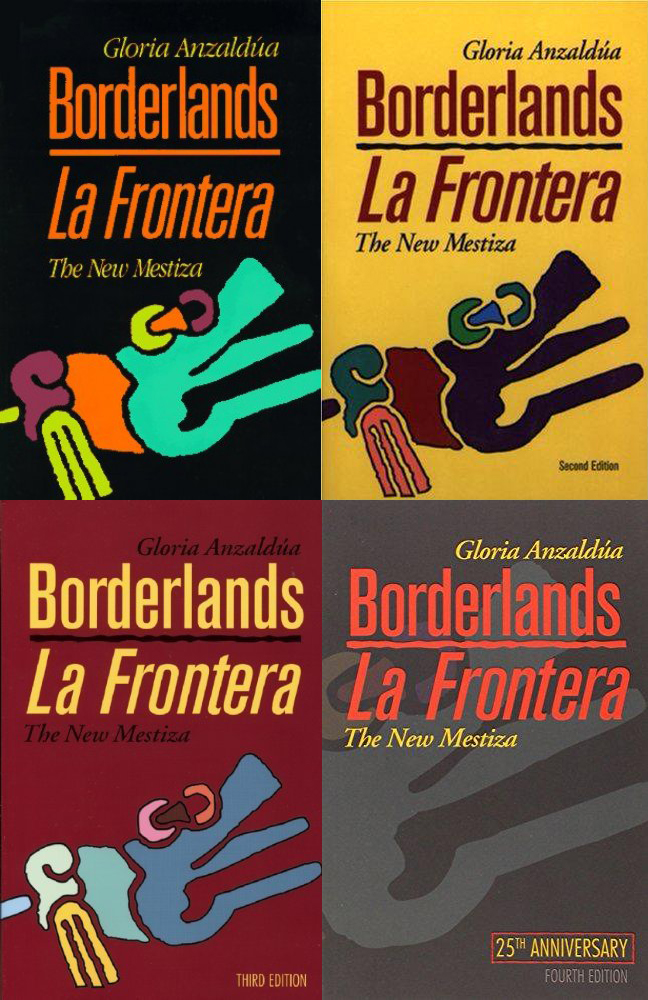

Covers © aunt lute books

The Project

This website is an attempt to represent the crucial linguistic materiality of Gloria Anzaldúa's work by demonstrating how much is lost when linguistic variance is. Of course, when encountering strange and challenging work, we can always translate difference away. But in so doing, the authorial foregrounding of difference is lost. This is especially true in the case of Borderlands, where the challenge to monolingualism and monoculture is part of the book's key thematic work.

This online representation of a portion of Anzaldúa's text represents the rigidity of borders, and the repressive ways they are used for enforcement. Readers are given the choice to "enforce" the border—to translate Anzaldúa's Spanish, and emphasize its difference and separateness. The result is a shutting out of Anzaldúa's English words. Separation is division. In order to read the text in its entirety, we have to accept that it exists in the linguistic borderlands, between languages, in a form entirely its own.

This project does not conceive of the text's position as border-straddling. The concept of the "borderlands" that Anzaldúa theorized has been taken up by many scholars as a call for transnationalism. This has been rebutted by other scholars (see Castillo 264), who point out that for Anzaldúa, the borderlands is explicitly a nation unto itself, "a third country, a closed country" (33). Anzaldúa takes pains to point out how her people have long lived in the same place, as national borders have moved around them.

Instead, a more productive way to think about Anzaldúa's cross-cultural navigation might be through the concept of "translingualism." As defined by Horner, et al., translingualism challenges the traditionally monolinguistic perspective of American culture (or any culture) by seeing "difference in language not as a barrier to overcome or as a problem to manage, but as a resource for producing meaning in writing, speaking, reading, and listening" (303). Anzaldúa is keenly aware of this linguistic difference—earlier in the excerpted chapter, she lists eight languages and dialects she speaks, only two of which are, by standard definition, a form of English. For Anzaldúa, language is crucial to identity, and the multiplicity of languages that shape her existence strongly informs the in-between-ness that she feels toward living under any of the labels that apply to her. There is the problem of nomenclature: what are you? ¿qué eres?, and there is the problem of representing that ambiguity in text, hence the hybrid linguistic form employed throughout Borderlands. This website attempts to actualize that ambiguity in an interactive form.

Beyond this, Borderlands displays a stunning degree of formal hybridity, using personal narrative, citation, from scholarship to folk song, theorizing, and poetry. The tension of these modes, languages, and identities is what fuels Borderlands in its scholarly and social activist work. Rather than submitting to the strictures of any one mode, language, or identity, in Borderlands Anzaldúa seeks to create a new translingual hybridity, what she later called "nepantla." But while she has hope for the future of this identity, it is for a day when "the inner struggle will cease and a true integration will take place."

While Anzaldúa's work is crucial to theorizing these oft-forgotten hybrid identities, living them is also a painful experience. For Anzaldúa, the "painfulness of hybridity" leads to incoherence, which is "neither inevitable nor acceptable, but coherence will only be achieved through conscious effort and political struggle" (Alcoff 257). Thus Anzaldúa refers to the process of the erasure of her Spanish and other native tongues as "linguistic terrorism," writing that "ethnic identity is twin skin to linguistic identity—I am my language. Until I can take pride in my language, I cannot take pride in myself" (81). This project tries to represent the pain and violence of such "linguistic terrorism" in stark terms, in order to represent the friction that is equally apparent to the translingual textuality of Borderlands.

The Website

This site was designed, in both presentation and function, to make the most of the digital medium in which it appears. In terms of its design, the color scheme is taken from the most recent (4th) edition of Anzaldúa's Borderlands, published by aunt lute books. While this cover repeats the graphic motif of the previous three editions (seen at the top of this page), its more somber presentation reflects the still-contentious and politicized aspect of much of Anzaldúa's work. As Norma Cantú and Aída Hurtado's introduction to this edition notes, Borderlands was banned in 2012 by the Tucson Unified School System in Arizona, "as part of its enforcement of a new law banning Mexican American Studies in its public schools" (3).

Far from serving as a tamed retrospective, then, the 25th anniversary edition of Borderlands makes clear that Anzaldúa's work is still as relevant as ever. This is also reinforced by my choice to use images of the existing U.S.-Mexico border wall as background for the site; the centuries-old struggle over where the boundaries lie, and how they can be used to enforce separation, is continually relevant, particularly in the rhetoric of the 2016 U.S. Presidential election.

In terms of the site's function, I sought to use the digital medium to its advantage by offering a reading experience that would not be possible in a printed book. The web has been hailed as an interactive medium, but readers have already interacted with books for centuries by writing in them, in the form of annotation, reaction, commentary, or even by simple forms of graphical marking, like underlining. Nevertheless, I wanted to create an interactive experience, not merely reproducing the page on the screen. Nor did I want to literalize the text, which meant that I needed to offer an interpretive reading; and I did not want to merely annotate textual or paratextual elements of Anzaldúa's work, so the presentation had to be illuminating in some way.

Ultimately, I decided to take a key aspect of Anzaldúa's writing, the formal qualities of her language, and to offer my readers a simple way to understand how these qualities are working, in a manner unachievable in printed form. Readers can, of course, read Anzaldúa's text as presented on this site. I would argue, however, that the most effective way that readers can experience the work presented here is not by reading at all, but through the visual and kinetic experience of turning the language diversity "on" and "off." The stark difference that this causes to the textual representation is an attempt to make clear the stakes of Anzaldúa's theoretical approach to language and identity, to emphasize how vital and necessary her work has been since its first publication.